In July, I had the honor of giving a keynote talk at PyCon Colombia 2025. This isn't exactly what I said on stage, but it is the script I was working from. Since some people prefer to read rather than watch a long video, I thought I would share it.

The full title of this talk is: "How to Think About Large Language Models for Open Source Software Development: A hype-free approach: That should still be relevant in a few months: That should work for most people"

Prologue

Disclaimer #1

Opinions are my own. Biases are my own, too. I know everyone’s experience in the world is different, and what works for me may not work for you.

Disclaimer #2

This is a “how to think about” talk, not a “how to”. There are plenty of “how to’s” out there – I don’t need to create another one. I want to leave you with some good questions, and seed some good hallway conversations. And maybe have a bit of a call to action.

But the other reason this talk is not a “how to” is that...

Disclaimer #3

This space is changing too rapidly to effectively give a keynote about. It seems like there is a new model or new layer on top or a new startup with a new solution every single day. I can’t possibly be on top of all the things people are doing in this space – if I say “we need a solution to X” in this talk, chances are someone already is working on that, I’m just not aware of them yet.

Thankfully I think I’ve found a framing to address this kind of rapid change. Back in the 90’s when I was studying computer science, the big battlefield was programming languages. There were all these languages that seemed to come and go – how do we know which ones to teach? The answer was – none of them. Focus on the things that are more fundamental – algorithms, data structures, distributed systems theory, etc – and use “teaching languages”, like “Turing, Eiffel, Standard ML of NJ” (anyone heard of those?) rather than the fads of the day. Students are left “learning how to learn”. I still think this was a good approach.

By treating LLMs as an unknown value, we can talk about general principles that are likely to remain relevant and ignore “news of the day” thinking. And whether LLMs improve or devolve, hopefully you are left understanding how to make decisions on your own to apply them to your own day-to-day work.

Disclaimer #4

I am not an expert in using LLMs for open source software development. Let’s break this one down:

First, what do I mean by “expert”? Anyone can become an “expert” in something with the right conditions. No one was born knowing “software development” – they just had the opportunity to spend time learning about it and doing it. That point may seem obvious, but there is a couple of decades of good research saying that most people believe that expertise is a fixed thing. And counter to that, it’s been shown that SWE teams that believe in the “growth mindset” – i.e. that anyone can become an expert in something with the right conditions – tend to perform much better than teams that believe in the “immutable” view of expertise.

Secondly, I say “LLMs” here because I want to make it clear that what I’m talking about are these generative tools based on large language models, plus the scaffolding like agents added on the side. I’m talking about this current new wave of things as distinct from the broader world of Data Science and Machine Learning. In particular, Artificial Intelligence is too overloaded, in my humble opinion.

And… I’m reducing the scope way down here to just open source software development. I’m not talking about drawing cartoons, doing drug discovery or any of the other things that generative AI may be used for. I’m also not talking about building software products that have LLMs inside them – that’s a whole other interesting space, but outside scope for today.

And I’m also talking about open source specifically, which is a bit different from, say, enterprise software development or other kinds of technical engineering. This is something I’ve been doing for over 25 years, so maybe I am an expert on this part, and based on that, I would argue that open source software development is actually a very complex set of social dynamics more than it is a technical activity. More on that later.

And when you put this all together, it’s clear that the number of experts who understand these very complex probabilistic tools (LLMs) and how they interact with these very complex social systems (OSS) is vanishingly small. In general, the intersection of software engineering and social or psychological systems has historically been extremely poorly studied (though there are some standout researchers in that area, such as Dr. Nadia Eghbal and Dr. Catherine Hicks), but when you are talking about tools that have only been widely available for, say, 2-3 years – at scale:

Experience in AI for software development is the new 20 years of Java experience: Meaning most of us are still figuring this out and working to “become” experts.

Disclaimer #5

LLM discourse is mired in anecdotalism and polarization: In software, it’s long been understood that “Works For Me” isn’t good enough. This is just a really, really old core scientific principle. It isn’t enough to say that “I took echinacea and my cold got better”, you would need to actually study the effects of echinacea on a larger population to ascribe any causal link that it’s a cure for the common cold. So it’s surprising to me that so much of the discourse around LLMs is still at the level of “I did something” and “it was amazing” or “it’s garbage”. Assuming good faith actors, both of those experiences are valid, but it doesn’t actually tell us much about how these systems really work when confronted with the real world at large.

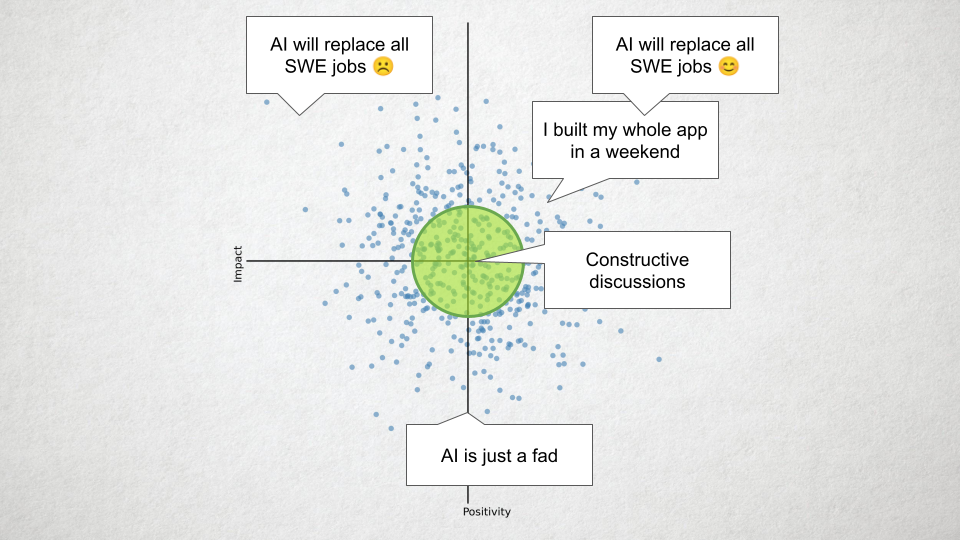

So, let’s suppose this is the universe of opinions or experiences with LLMs, plotted in a 2D space: on one dimension you have a person’s belief in its effectiveness and on the other how beneficial it will be. You might have one of these “anecdotes”, like “AI is just a fad”, “I built my app in a weekend” (this is the vibe coder – which I sort of take to be a straw man).

And over here you have “AI will replace all SWE jobs 😦”, and “AI will replace all SWE jobs 😃”. (The emoji are doing a lot of work here.)

But these are all extreme opinions. The really interesting ones are in this middle part, because this is where you can have conversations about moving the field forward. For my part, I think there is something useful here, and LLMs are here to stay, but I don’t yet know where it will end up for my own work or the world at large. But if we want to make them better and more useful, and work for US, specifically for open source software development, we need to be having conversations in HERE. One of the problems is that social media is designed to amplify the outlier opinions. LLMs are probably the biggest technological advance we have seen since the beginning of the “social media” era, and that’s not doing us any favors.

The other reason anecdotalism is so sticky is:

Disclaimer #6

LLM evaluation is really hard: The solution space of LLMs is just so large that it’s beyond any direct means to evaluate it at scale.

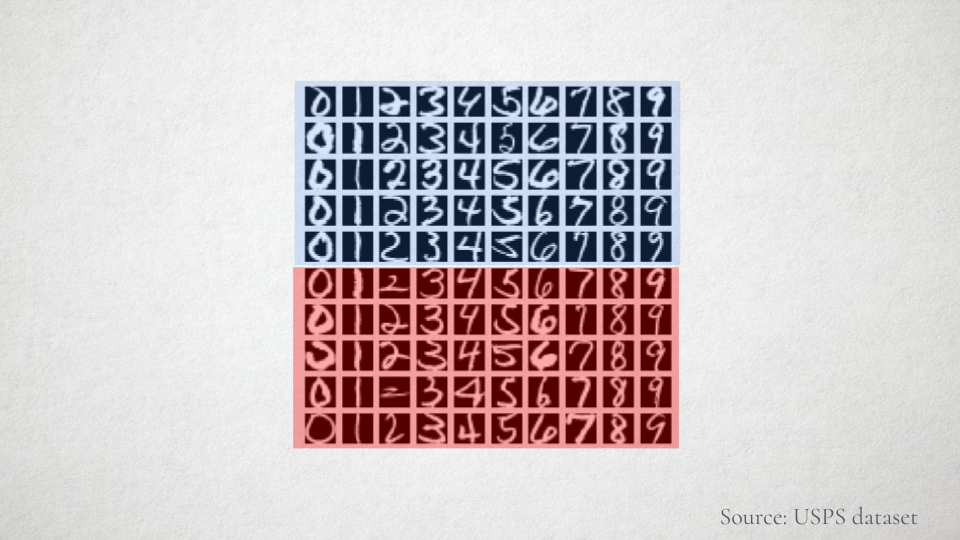

When I first started doing machine learning back in the late 90’s, the general approach was you took a data set (like a set of hand-written digits) and you trained your model on half of it, then you used the other half to evaluate how it was doing. (I’m hand waving over a lot of the detail here). This was all very straightforward and easy to understand, and, as long as you were ethical, hard to game. But with LLMs the expected solution space is so large, you can’t feasibly evaluate it in the usual way. Often people resort to horrorific distortions of the scientific process like using one model to evaluate another model. A lot of very smart people are working on making this better – but the state-of-the-art benchmark for software engineering tasks, SWE Bench, remains controversial, not just because there may be shenanigans going on by some players, but because the sophistication required to evaluate a model is equal to the sophistication required to create it in the first place.

Disclaimer #7

We all make mistakes: One thing I do find useful when talking about evaluating or benchmarking LLMs is the recognition that humans make mistakes, too. We shouldn’t be comparing machine output to some Platonic ideal of the perfect programmer – the perfect programmer doesn’t and can’t exist – there are always grey areas and tradeoffs everywhere you look, because software is built to operate in the real world, which is messy. But more importantly, because humans make mistakes and always have, we already have a set of processes and social constructs that we use to mitigate those mistakes, which can also apply to LLM-generated content. It is crazy to think we would take those guardrails off just because we have more automation in the loop. (More on that later).

My favorite bug

With that, let me take a detour and tell you about one of the favorite bugs that I caused. Back in 2007, I was working on matplotlib, and we had a problem that drawing scatter plots with lots of circles was just too slow. At the time, circles were drawn as polygons with a large number of edges, like 100. And filling a polygon with a lot of sides is rather slow.

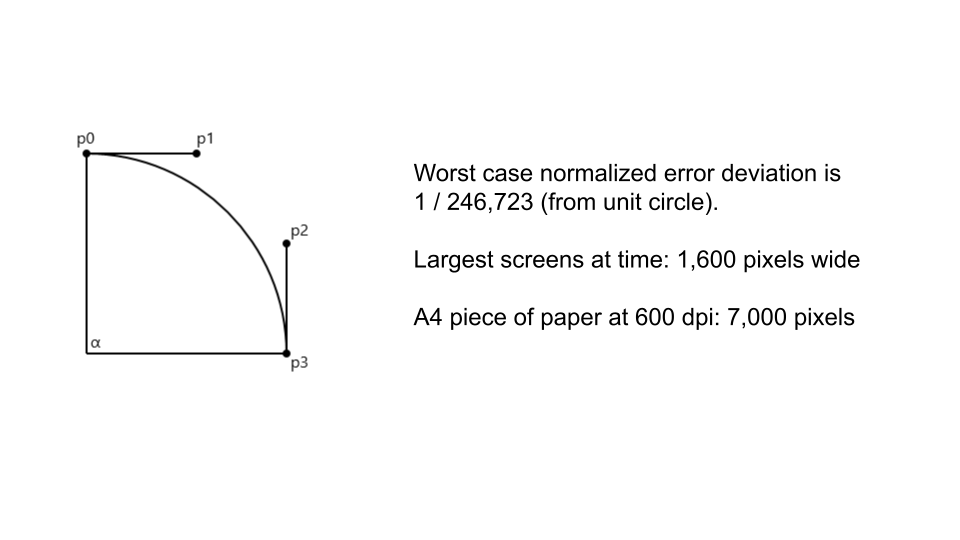

I found a paper that showed how circles could be approximated using 4 bezier splines instead, and all of the graphics libraries underpinning matplotlib understand how to optimize bezier splines rather well, so it’s a whole lot faster, and the paper even got into detail about how accurate this approximation was, and with some back of the napkin math it was clear that even if you drew a circle the whole size of a screen or a page, the inaccuracy wouldn’t be visible at all.

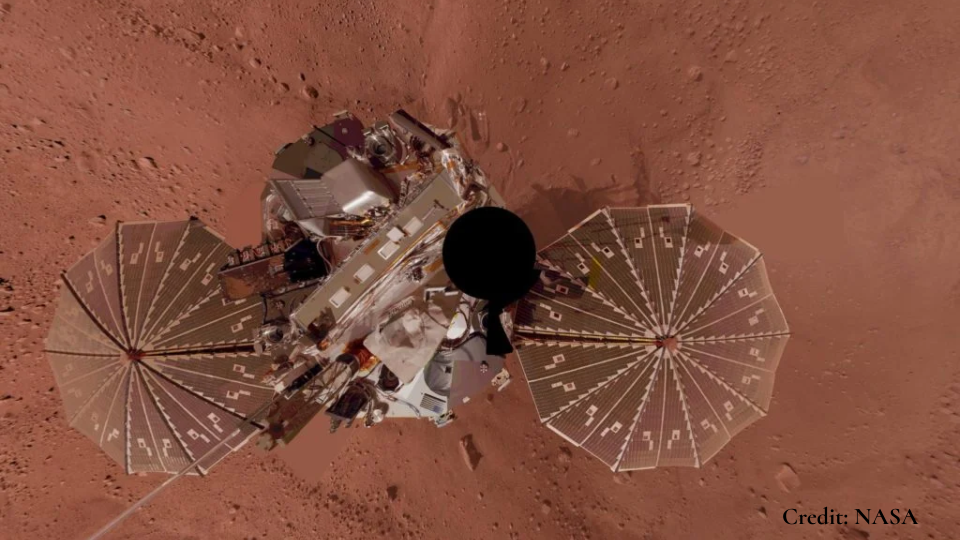

Enter the Mars Phoenix lander. The team managing the spacecraft at JPL was using matplotlib to plot its trajectory as it hurtled toward Mars at 12,000 km/h.

When you zoom in on the path, which is an ellipse much much larger than the circle representing Mars, the inaccuracy of the bezier curve was quite noticeable, and made it look as if the spacecraft would miss its landing entirely.

They weren’t using this for guidance (thank goodness!), but planned to use it on the big control room screens when they invited the press to watch the landing. “Oh, and, by the way, it’s already on its way, so please figure this out before it lands, we kind of have a hard deadline.”

Reverting the change wasn’t enough – the polygonal approximation also wouldn’t work at that scale (but it wasn’t as bad). I worked to figure out the solution – basically dynamically truncating the arc when larger than the viewport – the solution isn’t really the important part.

The moral of the story is – we all make mistakes and it’s really hard to anticipate all of the uses of software when you write it. The process – of not putting code into production until others have a chance to test it – saved its impact from being much worse. And the way it was fixed – in one place in matplotlib itself – meant that future NASA missions, and all other matplotlib users, could also benefit.

Back to the disclaimers.

Disclaimer #8

The most important disclaimer: Ethics matter: I want to acknowledge there are many ethical problems with LLMs, from climate-threatening energy usage, to amplification of bias, to labor market disruption, to intellectual property issues, and on and on. I will touch on a few specific ethical quandaries related closely to open source software specifically later on, but I can’t effectively cover all of the ethical issues in this talk. They are all important – anyone using LLMs should be aware of the pitfalls and be supporting those who are working on making it better. We can proceed with some things in parallel while we work on solving the problems, and proceed with different levels of caution, depending on our context. I don’t think “we should stop exploring these tools until we have all of the downsides figured out” to be a very practical position, but I’m also not going to say you are wrong if you choose to avoid the use of LLMs because any of these ethical problems are a dealbreaker for you. It’s important to me the open source community participates with everyone.

For my part, you may notice my slides are simple because I chose not to use generative art in my talks on ethical grounds – you are getting the true and full extent of my own artistic abilities here. I had some humans help with the content, but I didn’t use LLMs to help me write this.

The middle

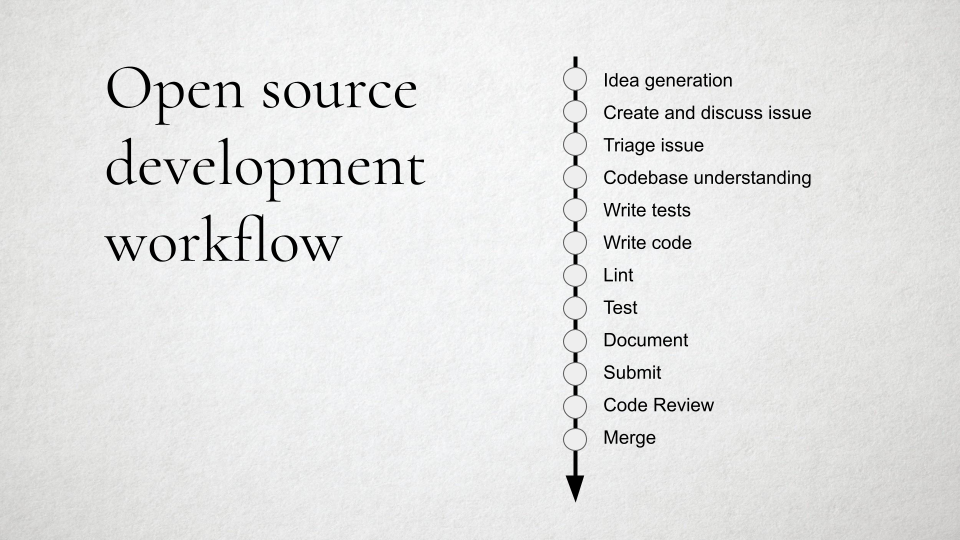

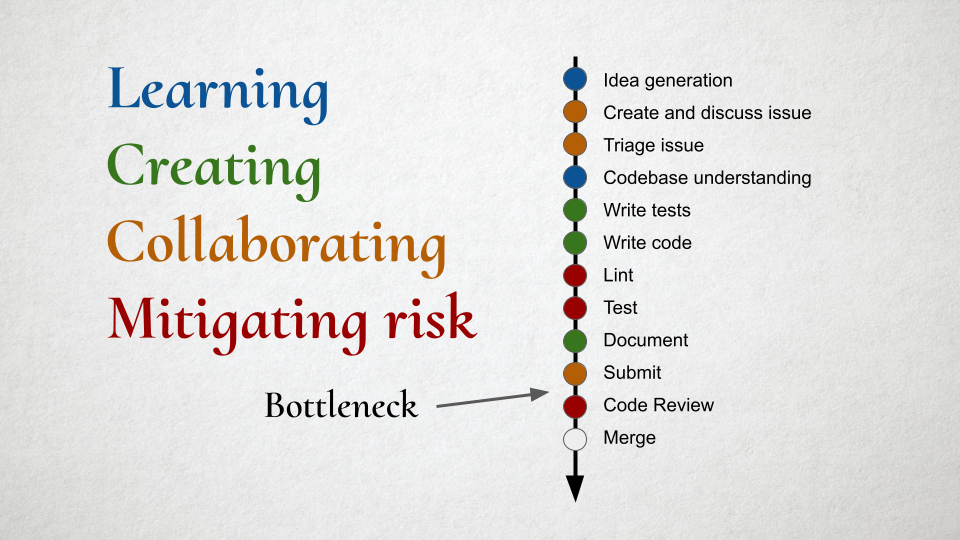

Open source software contribution workflow

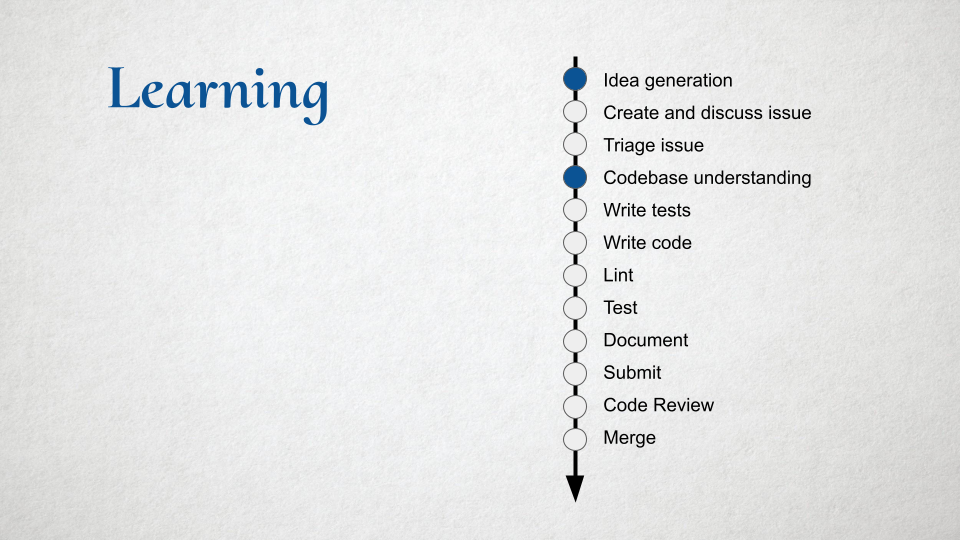

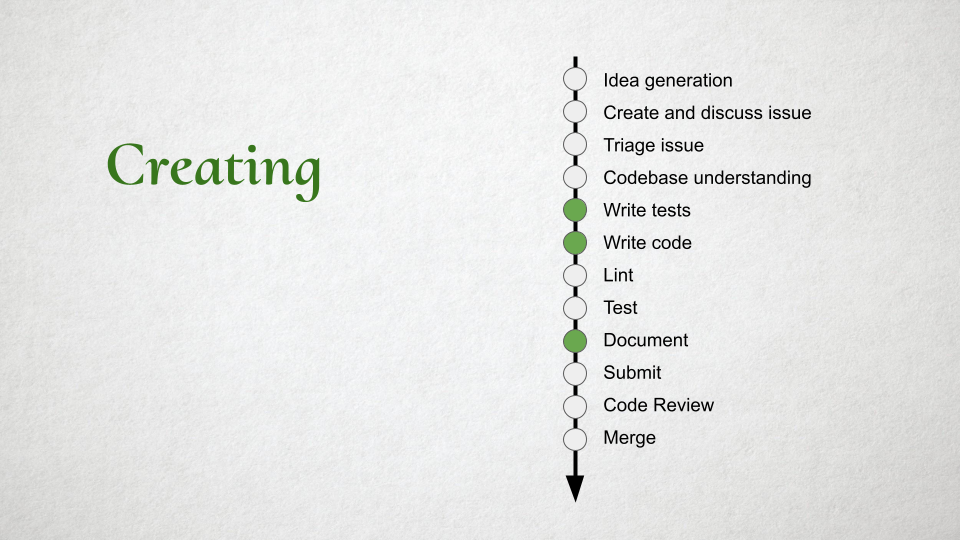

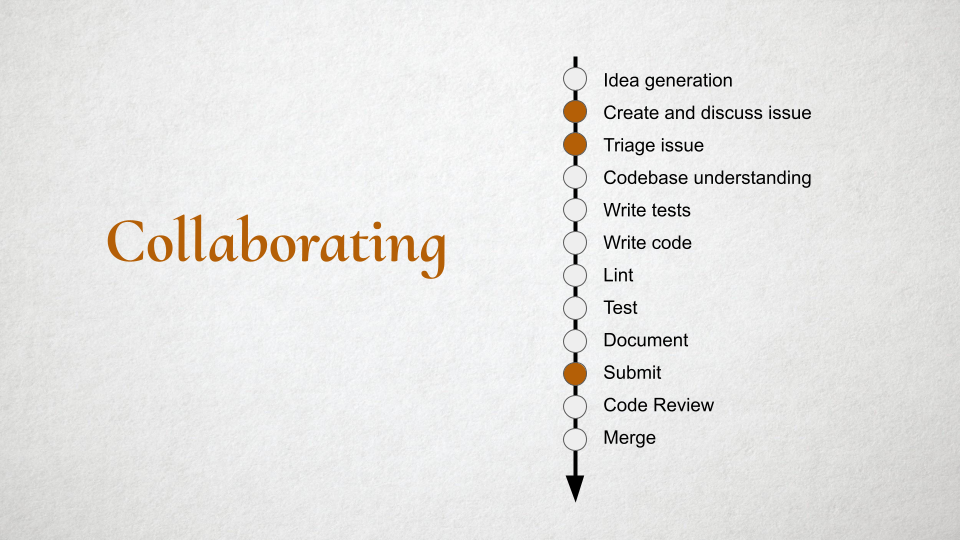

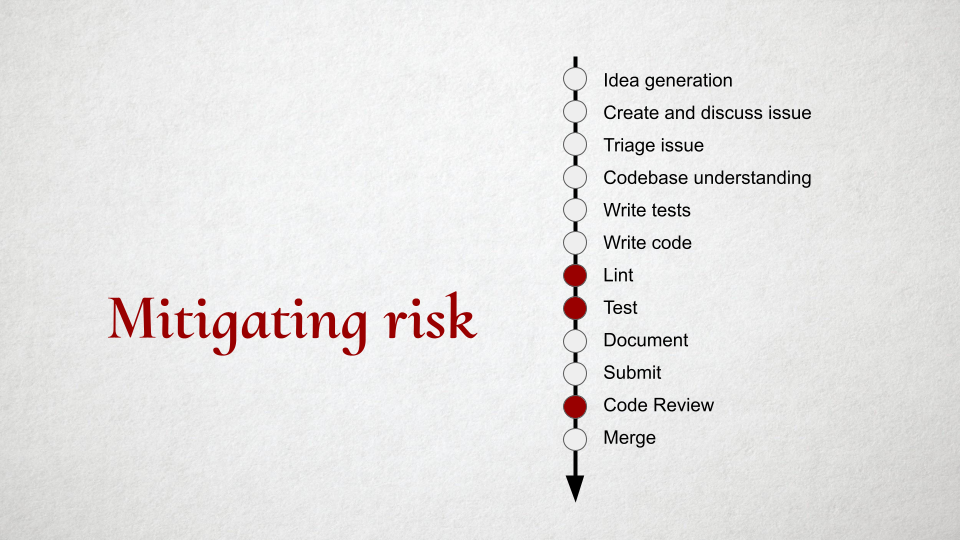

This is the usual workflow of adding a feature or fixing a bug to an open source project. It’s worth noting that even this is fairly new – GitHub has mainstreamed this workflow, but 15 years ago, everyone just threw their code in a pile and hoped for the best. But I think most serious open source these days has a workflow like this to mitigate risk and improve quality – with varying levels of rigidity based on context or project maturity.

You can actually use LLMs for any of these tasks, but how you approach them depends on the type of task.

For “learning” tasks, the LLM is acting like an augmented search engine, a summarization tool, or a research assistant. It can flag important things to learn or try and help to build a mental model of the current state of the code. There is low risk here – if it sends you down the wrong path, all you have wasted is time.

For “creative” tasks, you can use the LLM to generate the content, but ultimately, the human in the loop must take responsibility for the final result. “The LLM did this, it works, but I don’t understand why” is never going to pass muster – not just because it’s riskier, but because the end result needs to be understandable by other humans and LLM systems in the future. I might be reflecting my bias from working on long term projects here, but “building a quick short-term solution to throw away” doesn’t seem like we are advancing the art.

An important side note here is that LLMs seem to really pick up on documentation – “documenting code is the new SEO for LLMs”.

For “collaborating”, these are the points where the community comes together, so “keeping it real” is actually really important. I think it’s ok to use machine translation and grammar checking tools to help make communication more effective, but beyond that, you want to be human here. This is where things like personal trust, empathy and a sense of common purpose are built. If a maintainer starts to feel like they are talking to a machine, it undermines that. And I can’t really envision a world where LLMs are just chatting with other LLMs here.

It’s the “risk mitigation” steps where we need to retain the most caution. Even here, LLMs may be useful – for example, GitHub Copilot will review PRs for you – but it’s unlikely the LLM will have enough context both of the entire codebase or how it connects to the real world to meaningfully review an entire PR. I think today it’s more of an incremental improvement on linting – recognizing problematic patterns. So the LLM is basically “another signal in the mix” and not a “final arbiter of quality or taste”. Even with all of these combined filters of multiple humans and LLMs, my concern here is the mistakes and risks created by LLM-generated content may be subtly different from human-generated content, and the skill at identifying them will take some time to adapt to.

So, in summary, you can see that we can accommodate some risks HERE, because we are mitigating for it OVER HERE. If the use of LLMs made things worse, the mitigation may need to be different or harder in some ways (and we are going to need to adapt), but it doesn’t change fundamentally.

If the LLMs are improving throughput or “productivity”, the worry is that the volume of submissions will increase, open source library maintainers, already overwhelmed, will become burnt out. A number of projects have already seen an influx of AI generated slop pull requests. I think that for the most part “fully automated” or “malicious” issues and PRs will be filtered transparently by the platform – just like e-mail spam, it still exists but I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about it. But for hybrid things – where a human is using LLMs to complete work faster and not fully understanding the implications, that’s a real issue.

A more optimistic view of this is that the quality of PRs will improve before they even get to the maintainers, and maintainers will spend less time in back-and-forth getting them in shape. I, personally, have built a prototype to help first time bug reporters create better reports. It’s hard to get that without creating additional frustration. But I haven’t seen any evidence that we are at the point where LLMs are reducing the burden on maintainers, yet.

Wherever that ends up, one thing seems clear: From the maintainer’s side, the job will become even more about reading code, understanding the larger implications of changes, and connecting issues in the software to real human problems. My personal concern there is based on what we know about how humans learn – learning to be good at reading requires learning to be good at writing. For example, when we teach how to identify a good and well-reasoned essay, we don’t just have students read a bunch of essays, we teach them how to write an essay – a principle known as constructivism. It’s the same with code. So there is an educational / pedagogical challenge we have to help support the next generation of open source maintainers and help them become good readers when they may get less experience as writers.

On the contributor’s side, the advice I have is to stay real and human. Anything produced by LLM as a tool ultimately is still coming from you, so you need to learn enough to understand and stand behind it.

Don’t fall into the productivity trap: using LLMs is not about timing your tasks with a stop watch and watching seconds being shaved off. This is a Fordism (assembly line) view of software engineering, which doesn’t really apply to knowledge work. Instead, think of time scales of weeks not seconds. It’s not “it takes me X% less time to fix a bug”.

It’s things like – Are you forming stronger connections to the projects that you use? Are you finding yourself understanding them better? Do you find yourself tackling projects with confidence that seemed daunting before? Does building quick throwaway prototypes help you understand the correct “permanent” solution? You may never know if it’s the LLM that’s helping you, or just natural learning and the growing of expertise. (If the cost of the LLM subscription is not an issue) does it even matter?

Generative AI policies for open source software packages

I’m not the only one thinking about how LLMs fit into open source software development. One way to get a read on where the community is is by looking at the open source contribution policies. It’s early days, and therefore, unlike licenses and codes of conduct which have settled on a handful of standard models, LLM policies are mostly “one-offs”. When you look at some of them, it’s a sign that all open source isn’t created equal and they exist on a sort of “political spectrum”.

I'm just going to link to some policies here. I think they largely fit into the framework described above and highlight some of the concerns that OSS projects currently have.

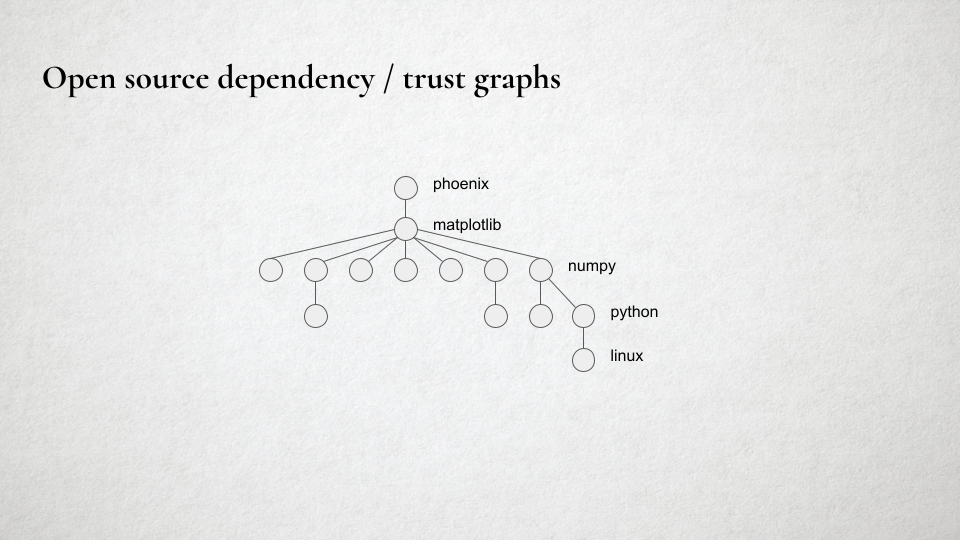

Open source graph of trust

Now let’s look at things from the perspective of a consumer of open source. Typically, you pull in some dependencies for your project, and you end up with a whole tree of secondary dependencies that get automatically pulled in. This forms a network of trust or reputation. In this example, I’m writing the Phoenix Mars lander software, and I depend directly on matplotlib. I heard it was a good library, maybe I met some of the folks at a conference and they seemed like nice people, so I trust it to do the right thing. I don’t really know or care what’s beneath that, but maybe I trust the matplotlib developers to care about that. Again, if one of these dependencies tanked in quality, the usual signals from the open source trust network will probably kick in. (Entire companies exist to help with this dependency safety problem, of course, if you /really/ need to be certain.) So there are some self-healing and mitigation of risk properties here as well. When you ignore the possibility of bad faith actors, I think LLMs represent an incremental, not existential, risk.

However, as the xz incident has shown – where a state actor impersonated a developer in order to take over an open source project and inject malicious code – using LLMs to convincingly impersonate developers at scale may soon be a real risk.

But let’s get back to my favorite bug. What if, back in 2007 the authors had access to an LLM, and they asked it to fix the bug? As designed today, that LLM tool is more likely to just create a workaround – in this case, having been told that matplotlib’s circle drawing code was buggy, it might attempt to write its own in the local project and just pass the result of that calculation off to matplotlib, rather than trying to report the bug or filing a pull request against matplotlib. These sort of workarounds are fine, of course – I don’t want to imply that we as busy software developers have to submit every bug we fix upstream. But the social system that makes open source work depends on the fact that a certain fraction of engineers do submit fixes upstream. If everyone started using LLM-based tools, and those tools never suggest contributing upstream, we’d very soon run aground. Not just because open source project quality wouldn’t move forward, but the solutions to the same problems may never make it back into training sets. And if you remember that the LLM was trained on open source projects to begin with, what it’s actually doing is syphoning off value from the open source commons to individual users of the LLMs, and ultimately, in the form of money, to the companies that sell access to LLMs.

Epilogue

We need tools that purpose-built for the social dynamics of open source software. The current wave of LLM tools are largely coming from large corporations and are built to support that model of development. We instead need tools that are built with the conventions of open source in mind. There are a few things holding back building the whole stack:

Models are mind-bogglingly expensive to build. By some outside estimates, ChatGPT will cost $2.5 billion dollars to train They are built from questionable rights in the training sets. While some of the models sell themselves as “open”, most are not “open source” by the classic definition – that they could be rebuilt from first principles from fully open data. It’s therefore currently too hard to “bootstrap” the whole stack in an open source way, and open source has historically been reluctant to build processes that rely on tools we can’t build from first principles The copyright claims on the output of the models may be problematic. Can we find a way to ensure that attribution is being correctly applied? That’s a hard problem because by the time the model is built it’s virtually impossible to track back to the source, but perhaps it is possible to do that as a post-processing step.

So, right now, I think it’s nigh impossible to build a model that would meet the traditional definition of open source. But we don’t need to wait to “get everything we want” – we can pick these apart and tackle them individually – it will be hard and expensive at first, but eventually economies may shift.

And while we tackle those problems, we can still treat the LLM as a black box and build tooling designed for open source processes all around it. I do believe the open source community has the opportunity to build something better that serves the commons, but we aren’t going to get there by standing on the sidelines.

Again, a lot of these things are already coming about. Let’s do more of that.

Existing processes for risk mitigation help, but will need to continue to evolve. The same systems that improve code quality with humans are still useful with LLMs, but they may change in nature, and they may require re-thinking how we approach validation of quality. To the extent that LLMs start training us, it will be in our ability to detect and remediate for their problematic content.

We have some real challenges to get there – some of them are technical, and some are pedagogical.

Collaboration and reputation matter now more than ever. Understanding how to work with other open source developers to meet the real world use cases remains the key skill, whether LLMs succeed or fail.

With the possibility of impersonation, or generation of “magical” solutions, personal responsibility, understanding, and reputation matter now more than ever.

I think that any additional skills you connect to software development matter more.

Conclusion: And I think that’s as good a segway as any to go forth to the conference and meet and chat in the hallway about the possibilities here.

Gracias por escuchar y buena suerte!

Comments

comments powered by Disqus